Iconoclasm and the 7th Ecumenical Council

The Second Council of Nicaea met in 787 AD (at site of the First Council of Nicaea over 350 years before) to address the issue of icons. The veneration of holy images and relics comes from the Old Testament tradition (including the images in the Temple, the veneration of the tombs of the Patriarchs, etc.) It was also present in Christianity from the beginning, as one can see from the earliest extant church at Dura-Europos (c. 235 AD).

The Second Council of Nicaea met in 787 AD (at site of the First Council of Nicaea over 350 years before) to address the issue of icons. The veneration of holy images and relics comes from the Old Testament tradition (including the images in the Temple, the veneration of the tombs of the Patriarchs, etc.) It was also present in Christianity from the beginning, as one can see from the earliest extant church at Dura-Europos (c. 235 AD).

However, after centuries of use, the veneration of icons was suppressed by imperial edict inside the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Leo III (717 – 741). His son, Constantine V (741 – 775), held a synod to make the suppression official in the Church.

The iconoclastic controversy first arose when Emperor Leo III ordered the removal of icons from public places in 726 AD. It would end in 843 AD when the Empress Theodora ordered the return of icons – event which is now celebrated yearly in the First Sunday of Lent as the Sunday of Orthodoxy.

There were two main reasons for the rise of iconoclasm. First, the superstitions of the emperor and his general; as Muslims started to win strategic battles, and press against Constantinople, they reasoned that God might be favoring them, and so the abandonment of images, which the Muslims did not use and indeed forbade, would secure God’s favor against the enemy. (This was a new manifestation of the pragmatism of the Roman emperors of old who sought to recover the ancient glory of Rome by crushing Christianity and going back to the old pagan deities.) Secondly, but less importantly there were a few church leaders who were concerned about abuses in popular piety.

Iconoclasm became a law in the empire for many years, the result of a rogue council in Hieria in 754 AD and this ultimately led to the Seventh Ecumenical Council in 787 AD (during the reign of Empress Irene). This Council met to affirm the belief of the Orthodox that veneration of the icons was proper and necessary for a correct understanding of the Incarnation of Christ, against those who held that icon-veneration was idolatry and that all icons should be destroyed (Iconoclasts). The council assembled on September 24, 787. It numbered about 350 members; 308 bishops (or their representatives) signed.

Exegetical basis for the lawfulness of the veneration of icons was drawn from Exodus 25ff; Numbers 7:89, Hebrews 9ff; Ezekiel 41ff; and Genesis 31:34, but especially from a series of passages of the Church Fathers; the authority of the latter was decisive. Following the Council other iconoclastic periods arose with another council in 815 AD until resolved in 843.

Although the issue was politically motivated (war against Muslims), the theological justification for iconoclasm came from the Old Testament prohibition against the worship of images. However, this has to be taken in context, since it is clear that the Old Testament has many accounts of images which the Patriarchs were commanded by God to construct, engrave, weave, etc., to assist in the Temple worship. The temple itself was full of images. Indeed, this included images of “things in heaven and on earth:” cherubim, bulls, trees, etc. In addition, to combat pagan worship, the Israelites were taught that, contrary to the anthropomorphic images of local deities, YHWH is infinite and invisible, and therefore He cannot be visually represented.

After the Incarnation, the issue in the 8th century became Christological: whether representing Christ, who is God incarnate, would constitute a violation of the commandment not to represent YHWH.

A related question was whether representing the humanity of Christ (without the possibility of visually representing his Deity) would constitute a division of His humanity from His divinity – and thus a return to Nestorianism, a heresy condemned in the Third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus, 431 AD). On the other hand, if His humanity and divinity are both represented together, then the question would be whether this would constitute a confusion of his natures, and therefore a return Monophysitism – another heresy condemned centuries before, in the Council of Chalcedon (Fourth Ecumenical Council, 451 AD)

The iconophile response (especially through the work of St. John of Damascus) to the iconoclasts’ dilemma emphasized a few key points:

(a) The icon represents neither Christ’s divine nature nor his human nature, but his Person which unites in itself these two natures. This is a simple restatement of the reasoning of the Council of Ephesus (431) against Nestorianism: because of the hypostatic union, Mary is not the mother of a nature (human or divine), but the Mother of a Person, who is God.

(b) Christ assumed all the characteristics of a human being (except sin), including the ability to be physically located, circumscribed, and described –thus making images of him possible.

(c) We don’t divide or confuse natures in icons but rather pass honor through them to the prototype – the Person of Christ.

(d) The Church does not teach the worship (latria) of icons; that is reserved for God alone. But rather it venerates (or confers proskynesis) the icons as one would venerate any loved one. Proskynesis is a very ancient practice (which extends to this day in many cultures) of honoring, often with bows, someone of higher rank, including family members. This veneration gives honor to Christ, the Theotokos and the saints whom the icons represent. The honor passes through them to those worthy of honor.

(e) In addition, the fallacious false dichotomy (the either/or dilemma) put forward by Constantine V had the appearance of a work of sophistry. To say it is improper for us to see images of Christ is the same as to say it was improper for his disciples to see him. This cast some doubt over the apparent religious nature of the emperor’s Christological concerns.

Between 726 and 775 AD thousands of Christians were killed, especially monks and nuns, because they held on to their icons. The Seventh Council in 787 AD theoretically put an end to this. The Council affirmed that icons are to be honored and not worshiped, placed restrictions on what would be considered an icon and how it was to be written (painted) and honored, and showed the theological necessity to represent Christ. According to the Ecumenical Council, a rejection of images was, in fact, a rejection of God incarnate in Christ, and communicated in the Holy Spirit.

The Council determined:

“As the sacred and life-giving cross is everywhere set up as a symbol, so also should the images of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the holy angels, as well as those of the saints and other pious and holy men be embodied in the manufacture of sacred vessels, tapestries, vestments, etc., and exhibited on the walls of churches, in the homes, and in all conspicuous places, by the roadside and everywhere, to be revered by all who might see them. For the more they are contemplated, the more they move to fervent memory of their prototypes. Therefore, it is proper to accord to them a fervent and reverent adoration, not, however, the veritable worship which, according to our faith, belongs to the Divine Being alone — for the honor accorded to the image passes over to its prototype, and whoever adores the image adores in it the reality of what is there represented.”

The iconoclast controversy reflects not only a concern for Christology, but also a related concern for the value of matter and the body, and the relationship between the visible and invisible worlds, which were for the Byzantines equally real. Gnosticism was an ancient heresy that separated the physical from the spiritual, and argued that Christianity had nothing to do with physical things. Again, this had been condemned from the 1st century.

Inasmuch as iconoclasm brought together many different heresies that had already been addressed, it also differed from all earlier heresies in that it originated, not from the bishops and lower clergy, but from the rulers themselves. It was a classical case of the State telling the Church that it needed to change its beliefs.

Through iconography, the Church continued to affirm the goodness of the material creation. Matter was recognized as worthy means of expressing and proclaiming sacred realities, since God, through his Incarnation, has deified matter. The Spirit, who gives life to all things, “the Spirit of Truth, who [is] in all places and fills all things, the treasury of good things and the giver of life” sanctifies matter by making it Spirit-bearing. The Incarnation, having given to matter a new function and glory, legitimizes art, and even necessitates it.

Also the purpose and meaning of the incarnation was seen as the ‘deification’ of humanity; since matter (through the Incarnation) has become a vehicle of salvation (i.e., a means by which to attain salvation, rather than an obstacle to attaining it), a defense of icons was essentially a defense of the foundation of the Christian faith.

This connection between icons and soteriology was famously expressed by John of Damascus: “I have seen God in human form, and my soul has been saved.”

The attacks, however, did not abate. Emperor Leo V renewed the iconoclastic policies in 815 AD. He ordered that icons be placed out of reach of the people so they could not be venerated or kissed. On Palm Sunday in 815 AD, St. Theodore the Studite led a procession through the main part of Constantinople with icons against the imperial decree. This was met by attacks, tortures and murders.

Veneration of the holy icons was finally restored and affirmed by the local synod of Constantinople in 843 A.D., under the Empress Theodora. At this council, “in thanksgiving to the Lord God for having given the Church victory over the iconoclasts and all heretics,” the celebration of the Triumph of Orthodoxy was established on the first Sunday of Great Lent, which is celebrated yearly by the Orthodox Church throughout the world. Thus, with the resolution of the Iconoclast Controversy, the Age of the Seven Councils came to an end.

A great history of the use of icons in the Church. If you don’t mind I’m gonna copy this to my own blog (If that’s cool. I’ll give you credit, I promise)

Of course Jeremiah, anytime. Glad it was helpful.

Along with whatever determinations each Council promulgated, they all established canons as well. The canons are not on the same level of authority as the theological determinations of the councils, since the determinations are dogmatic affirmations of the faith and cannot be changed. The canons, however, address temporal and local issues that are part of the “oeconomia,” or the practical administration of the Church. I wanted to list the 22 canons promulgated at this Council, so we have a glimpse of interesting issues going on at the time.

Especially interesting to me are canons 2, 3, and 9.

Canon 1: The clergy must observe “the holy canons,” which include the Apostolic, those of the six previous Ecumenical Councils, those of the particular synods which have been published at other synods, and those of the Fathers.

Canon 2: Candidates for a bishop’s orders must know the Psalter by heart and must have read thoroughly, not cursorily, all the sacred Scriptures.

Canon 3 condemns the appointment of bishops, priests, and deacons by secular princes.

Canon 4: Bishops are not to demand money of their clergy: any bishop who through covetousness deprives one of his clergy is himself deposed.

Canon 5 is directed against those who boast of having obtained church preferment with money, and recalls the Thirtieth Apostolic Canon and the canons of Chalcedon against those who buy preferment with money.

Canon 6: Provincial synods are to be held annually.

Canon 7: Relics are to be placed in all churches: no church is to be consecrated without relics.

Canon 8 prescribes precautions to be taken against feigned converts from Judaism.

Canon 9: All writings against the venerable images are to be surrendered, to be shut up with other heretical books.

Canon 10: Against clerics who leave their own dioceses without permission, and become private chaplains to great personages.

Canon 11: Every church and every monastery must have its own œconomus.

Canon 12: Against bishops or abbots who convey church property to temporal lords.

Canon 13: Episcopal residences, monasteries and other ecclesiastical buildings converted to profane uses are to be restored their rightful ownership.

Canon 14: Tonsured persons not ordained lectors must not read the Epistle or Gospel in the ambo.

Canon 15: Against pluralities of benefices.

Canon 16: The clergy must not wear sumptuous apparel.

Canon 17: Monks are not to leave their monasteries and begin building other houses of prayer without being provided with the means to finish the same.

Canon 18: Women are not to dwell in bishops’ houses or in monasteries of men.

Canon 19: Superiors of churches and monasteries are not to demand money of those who enter the clerical or monastic state. But the dowry brought by a novice to a religious house is to be retained by that house if the novice leaves it without any fault on the part of the superior.

Canon 20 prohibits double monasteries.

Canon 21: A monk or nun may not leave one convent for another.

Canon 22: Among the laity, persons of opposite sexes may eat together, provided they give thanks and behave with decorum. But among religious persons, those of opposite sexes may eat together only in the presence of several God-fearing men and women, except on a journey when necessity compels.

Marcelo, very interesting history. God seems to be teaching me many things these days about the broader scope of Christianity. I come from a non-denominational protestant American background. I have experienced very little in the way of traditional icons, but one could argue that modern worship and Christian music in general are equal to the icons of so long ago. What do you say to this? Must icons be rooted in ancient history and constantly venerated?

Also, Canon 9 equates iconocasts with heresy. Gideon’s ephod was fine until he died and then it became an idol. I believe the same is true when anything is set up to represent or give glory to God and then that which is put in place becomes the focus rather than the conduit. At that point, the thing which was a conduit to give God glory becomes an idol. According to Canon 9, have I just committed heresy?

Jeff, these are good questions. Let me address a few points.

First, as I stated in the comments, each Ecumenical Council made determinations concerning the Faith, and these are unchangeable and binding upon all Christians, since they were made by all the representative Bishops of the whole Church in the whole world. Also, all the Councils had to be ratified by the acceptance of the Christian people as well; obviously the Ecumenical Councils were ratified not only by all the Bishops but also by all churches.

The canons, however are not timeless, binding statements on the Faith; they are administrative decisions that might or might not endure for centuries, and might or might not be changed according to the circumstances.

In this particular issue, canon 9 speaks of the writings against iconography, which were considered heretical simply because the use of icons for worship was deemed to be Orthodox practice. So for example, the first Ecumenical Council determined that Jesus Christ was of one essence with the Father, and so any writing denying this (whether Modalist, Docetic, Apollinarian, Arian, or of any other variety) was considered heretical, and therefore removed from any official teaching of the Church. So also now in the 7th Ecumenical Council concerning icons, since the Council determined that images of Christ are images of neither nature, but of the Person, who is God incarnate, etc. (see above).

So in this case heresy is to understand exactly what the council is saying about the nature of Christ, and about the propriety of venerating the representations of the Prototype; and then to write or accept the writings and teachings in contradiction to what the entire Church determined. Such writings were considered to go against the Faith and therefore heretical.

Now concerning the question of whether “modern worship and Christian music in general are equal to the icons of so long ago” it would seem to me that they are very different things. First of all, icons are present, ongoing realities, not something of “long ago.” People paint icons every day all over the world. There are even miracle-working icons, as recognized by the authorities of the Church and thousands of people that have witnessed and experienced such miracles – and some of those icons were painted very recently. (Obviously miracle-working icons are not the rule, that’s why they are exceptional). There are certain rules and guidelines to the painting (or writing) of icons, but anyone able to do so can do it, and they do it everyday, whether in monasteries or common households.

Icons are very different than “modern worship” and “Christian music.” First of all even calling music as “worship” (as in, “this is the worship band,” or, “we will have worship and then the sermon”) is something entirely foreign to the vocabulary of the Church. We worship God with our lives, we worship God through prayer, and we worship God especially in the Liturgy, which includes, psalms, hymns, prayer, the proclamation of the Gospel, the Eucharist, kneeling, bowing, crossing ourselves, receiving the blessing from the priest, blessing one another and God, etc.

At any rate, “Christian music” (I don’t even know what that is; are Bach’s cantatas “Christian music” or only Amy Grant? Is Mozart’s music not divine when it does not mention God, whereas a crappy heavy metal band who mentions Christ in a favorable way is “Christian music”?), in the modern sense of the word, seems to be a vehicle contrived to elicit some emotion in conformity to the world’s current popular music. If people like pop music of whatever kind, with guitars and drums, colored light systems and a fog machine, and seem to be moved by it, then play that at church, stick some “Christian” lyrics on it (whatever that means), and play it before the sermon, and then a little bit when the pastor is wrapping up. Then people be moved by it, with hearts warmed up to hear the Word. It’s often nothing more than a manipulation of emotions (perhaps not always).

I don’t want to get into a discussion about modern “Christian” music, but strictly speaking they are not like icons because icons are created as to depict particular people in particular situations, with a great deal of theology involved in them, and they are timeless windows “to be embodied in the manufacture of sacred vessels, tapestries, vestments, etc., and exhibited on the walls of churches, in the homes, and in all conspicuous places, by the roadside and everywhere, to be revered by all who might see them.” They are to be revered, “for the more they are contemplated, the more they move to fervent memory of their prototypes.” They are visual Gospels. Therefore, “it is proper to accord to them a fervent and reverent adoration” (or veneration, not worship). Icons are timeless, they depict timeless elements in them (they represent timeless heaven), and they are not bound to any particular culture or time. Icons are generally not done to depict reality as a realistic painting, but to remind us that the prototypes they represent are no longer bound by time and space, but have transcended this world, which is what we begin to do even in this life.

As to Gideon’s ephod, it has nothing to do with icons for a few reasons. First, it was not depicting the Incarnate God because He had not become incarnate yet. Second it was an object of idolatry (not veneration of YHWH) from the very beginning, not just after Gideon died, as you state. We read that “Gideon made an ephod of it and put it in his city, in Ophrah. And all Israel whored after it there, and it became a snare to Gideon and to his family” (Judges 8:24). So it was an amulet, copying the pagan worship of the pagan nations around Israel. It was unlawful and idolatrous to begin with, not something good that was perverted later.

Maybe a related argument would be that it is then better not to have anything physical mixed in the faith and piety of God’s people, since anything tangible can be turned into an idol. Well, it is true that anything tangible can be turned into an idol. But God sanctified matter, and to reject that is to fall into Gnosticism, heresy which was condemned even from the New Testament (see article). Also, this would eliminate all physical things that God himself has instituted in His worship, since the Ark of the Covenant, for example, could become an object of idolatry, if the people forgot about the living God and turned it into an idol.

So could all other things that God himself instituted, such as the temple, the Cherubim covering the Ark, the Cherubim depicted in the curtain of the Holy of Holies, the table of Bread with the wine in the Temple, the altar of incense, the bulls holding the water right outside the building, the High Priest’s ephod, his turban, his golden sash, the 12 precious stones on his breast plate, and even the high priest himself; and so could Paul’s handkerchiefs and aprons, or printed Scriptures, or the water of Baptism, or the hands that were laid on someone to impart the Spirit or to heal a sickness, or crosses in church, or altars, or pastors, or rock’n’roll worship leaders, etc. I think it’s easy to see the point. As you say, anything “which was a conduit to give God glory [can] become an idol,” even the things God himself has instituted.

The solution is not to remove what God has established through his Church, or to remove things or people that can be idolized, but to remove idolatry, whenever there is any. Again, if people chose to turn the Ark of the Covenant into an idolatrous item (as they did a couple of times in Israel) the solution was not to destroy it; God himself appointed it. The solution is to turn people to the worship of the living God.

At any rate, from experience and from historical knowledge, I don’t think idolatry of icons has been a problem in the Church at all. The problem in the Church (or any church) has always been the opposite of devotion to Christ and his Church (including devoted veneration of icons) – it has been lack of Scriptural knowledge, nominalism, lukewarm faith, sinful lives, lack of confession, infrequent communion (and the lack of proper preparation), lack of faith and love for God, lack of love for one another, materialism, worldliness, etc. I can assure you that where those things are, icons are not being fervently revered.

Hope this helps.

Your original argument holds some merit. God has honored the physical world, so it is right and appropriate to make things to help us remember and understand Scripture. To the illiterate and young Children, a picture Bible is invaluable. To those who can read, an ornate and detailed picture can help one remember and understand at a different level using what we call today different learning styles.

When God called the Israelites to build the , He called forth the skilled craftsman of every trade. He also called forth the skilled musicians. Beauty is important and valuable in God’s economy, so the things we make to honor him should be beautiful, be it a picture or a song. The arts evoke imagination, creativity, emotions. All things God honoring. You criticize music created to draw believers to a deeper understanding of God. Many of the songs of bands like Third Day and The David Crowder Band are filled with deep theological meaning. I am bless tremendously by them, and your summary judgement and execution of these things is uninformed.

Let’s turn the corner and talk about icons.

“So neither he who plants nor he who waters is anything, but only God who gives the growth…. So let no one boast in men. For all things are yours, whether Paul or Apollos or Cephas or the world or life or death or the present or the future—all are yours, and you are Christ’s, and Christ is God’s.” (1 Cor. 3:7, 21-23)

The original, authentic, and ancient church at Corinth had a problem. They were venerating those that brought the Gospel to them and Paul had stern words for them. Many of your points center around venerating Icons that focus our eyes on Jesus. I find no fault in that. In fact, you convinced me that this would be a good thing to have in my house. A piece of the historic Church to remind me of the multiple facets that make the Church the Jewel that is Christ’s bride.

So I did a little shopping online and was dismayed by what I found. On http://religiousicons.com there are 211 icons featuring various saints, 186 featuring Mary, and 47 featuring the Lord. That’s 23% Christ and 77% non-Christ. They have six featured items. Three of them are Mary, and the other three are saints that I’ve never heard of: Phanourios, Alexander, and Gerassimos.

I was curious to learn more about one of them, so I looked up Phanourios.

“Little is known about St. Phanourios’ life and time. We do not know when or where he came from. The saint’s icon was the only icon discovered in the demolished ruins of a church in Rhodes, and what we do know about him was gathered from that icon. We know that he was a soldier and a martyr that suffered several different tortures. People pray to Saint Phanourius to help them recover things that have been lost, and because he has answered their prayers so often, the custom has arisen of baking a Phaneropita (Phanourios-Cake) as a thanks-offering.”

So the only things we know about this guy we learn from the picture and from where it was found, yet people pray to it/him and find things they’ve lost, so he must have been a great guy. Let’s make a cake as a thanks-offering. No that’s not idolatrous.

This is a prime example of why Icons put a bad taste in my mouth. They may be pretty in an ancient art history sort of way, but they aren’t for me. Does that make me a heretic?

It may be good cake, but is it good theology?

Saint Phanourios (pronounced “fan-OO-ree-os”) is to the Greek Orthodox what Saint Anthony is to the Catholics: the patron saint of lost things. But here’s the twist: this saint has a sweet tooth. Greeks bake, bless, and give away this humble nut-and-spice cake, also called a phanouropita, in return for the saint’s help to find something that’s missing. During my own year-long quest with the phanouropita, a friend’s grandmother showed me how to make the following version of this traditional Greek cake, which she likes to enjoy with morning coffee. Of the many recipes I’ve tried, it’s my favorite, because it’s so forgiving. The batter is easy to make by hand, and it’s all about proportions, which means you can use any reasonable measure (a coffee cup or drinking glass) in place of a standard cup. To my mind, the recipe’s looseness perfectly captures the spirit of Greek home cooking and offsets the formality suggested by Church and Saint. It also adheres to the traditional nine ingredients. (If you cheat just a little and count the cinnamon and cloves together as spices.) One unbreakable rule: Before you begin, take a moment to think of something you’d like Saint Phanourios to help you find—keep this in mind as you make the cake.—Allison Parker

LC Date with a Saint Note: If you’d like some divine company in the kitchen, print this image of the icon of Saint Phanourios and keep it within sight as you make the cake. Be warned, though—this alone won’t bring you what you seek. Sincerity is everything when conversing with a saint.

convert Ingredients

1 cup vegetable oil, plus more for greasing

1 cup freshly squeezed orange juice (from about 3 oranges)

1/2 cup brandy

1 cup sugar

1 cup chopped walnuts

4 cups all-purpose flour, plus more for dusting

1 1/2 teaspoons baking soda

1 1/2 teaspoons baking powder

1 1/2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon ground cloves

Powdered sugar for dusting (optional)

Directions

1. Adjust an oven rack to the middle position and preheat the oven to 375°F (190°C) degrees. Oil the bottom and sides of a 9-inch round cake pan (or a Bundt or loaf pan of equal volume). Dust the pan with flour, tap out any excess, and set aside.

2. In a large bowl, whisk together the oil, orange juice, brandy, and sugar until thoroughly combined. Mix in the chopped walnuts.

3. Sift together into a medium bowl the 4 cups of flour, baking soda, baking powder, cinnamon, and cloves. In small batches, add the flour mixture to the brandy mixture, whisking vigorously as you go. Continue whisking until completely combined. The batter will be very thick and slightly gummy—not to worry. (If it seems impossibly thick, you can always do what I do and splash in another tablespoon of brandy.) Tradition dictates that you’re supposed to whisk for 9 minutes by hand. Good luck.

4. Scrape the batter into the prepared pan. Before putting the cake into the oven, pause to say whatever kind of prayer you feel comfortable with as you focus on the thing you hope to find. (Greek Orthodox women make the sign of the cross, but the cake will not suffer if you skip this step.)

5. Bake the cake until the top looks hard and golden brown and a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean, about 40 minutes. Let cool in the pan for 5 minutes, then remove the cake from the pan and let it cool completely on a wire rack.

6. Traditionally, the cake is now given away whole or cut into nine pieces and shared with others. If you’re serving the cake at home, you may want to sift a little powdered sugar over the top of the cake before slicing. The cake dries out easily, so if you do cut into it, make sure to wrap any leftovers well in plastic and foil, or store in an airtight container.

© 2010 Allison Cay Parker | Photo © 2009 Alice L. Parker. All rights reserved.

Read more: http://leitesculinaria.com/51410/recipes-greek-cake.html#ixzz1SWO8h16m

Jeff, first, as I said, I will not enter into a discussion about “Christian music.” That is not the topic of the post. You say that I am “uninformed,” but as a former professional guitar player, who has played in a “worship band” and has recorded cds with a “worship band;” and also as a former minister, who was in church leadership for years before being ordained, and then pastoring a church for another few years, I think that uninformed is the last thing one can say about my opinions on this topic, regardless of whether I’m right or wrong.

Second, the question of heresy has already been addressed in my comment above. Please read it again.

Third, the subject of the post was to give a historical and theological account for the decisions of the 7th Ecumenical Council on iconography. Now, you are asking for reasons for your use or not of icons. This is a related but different topic, and I can’t address that here to a very helpful extent.

There are several good books on iconography. It seems you didn’t even know the Church has always made icons of many people. So we are starting from scratch here. Let me say first of all that I have no intention of convincing you to have icons. You are not Orthodox, so even if you acquire any icons, you might need to learn a bit more about how they integrate into the spirituality of the Church. Icons are not pretty decoration pieces.

Obviously there are icons of thousands of saints. It’s like pictures we have of loved ones. Icons depict Christ, the angels, the Theotokos (the Mother of God), and many, many saints, martyrs, etc.

They are, first of all, models of the Christian life, in their own context and capacity. Many died for the faith, or suffered greatly. Others were great teachers. Others yet have some particular aspect of their life that model particular ways in which faith, hope and love are made present in the world.

For example, consider Santa Claus (the commercial icon) over against the real Santa Claus, or, Saint Nicholas of Myra – read about his life, his works, his helping the poor, his participation as a Bishop in the First Ecumenical Council – and then you’ll understand why we have icons of St Nicholas and teach the faith to our children through him instead of a guy who flies with reindeer from the North Pole.

So looking at a site and finding out how many icons are there of such and such saint and how many of Christ is about the most fallacious and pointless thing you can do. It’s like saying one must not love Jesus very much since he constantly asks his 25 friends to pray for him to the Father, instead of only asking Jesus. That’s just ridiculous.

The Church confesses the Communion of Saints. If you are a non-denominational Christian who has not looked into what that has meant in history, you might need to learn a bit on that before you can understand icons better. I can’t just write a book about it here. Suffice to say that from the early Church there was the recognition that death has been abolished by Christ, so those who have “fallen asleep” are not only in the presence of Christ, but they also continue to serve Him and us in ways even greater than before their repose, because now they are not hindered by human weakness, time, space, sin, or any other thing. We are not cut off from them, and they are not cut off from us. We are all joined in Christ, as his Body, in communion. Death has not separated us because Christ destroyed death. So, if they prayed for and assisted us before reposing, they do so much more now, and in the (now heightened) capacity that is their own, i.e., taking into account their gifts, interests, and so on.

Again, if this is not something that you have studied, please do so with the many resources available; do not ask me to turn this comment section on an exposition of the meaning of the Communion of Saints or any other potential rabbit trails we can get here. One can only do so much at a time in a comment section.

By the way, the situation in Corinth has absolutely nothing to do with the veneration of icons. The problem there was division in the Church. People were creating factions. Icons are not factions. They are the opposite – they demonstrate how we are all the Body of Christ, united in him, and following him in our particular lives, with the assistance of one another.

In fact St Paul often told people not only to imitate God, but imitate him, and imitate those who imitate him and imitate God as well. See 1 Cor. 4:16, 11:1; Eph. 5:1; 1 Thes. 1:6; 2:14; 2 Thes. 3:7-9; Hebrews 6:12; 13:7. This is what icons, among other things, help us do – which is just the opposite of the factions in Corinth.

When I was Chrismated, I took St John Maximovitch as my patron saint. Patron saints are like spiritual fathers and mothers, who model the faith to you in a way that speaks to you particularly. St John was a bishop here in San Francisco. He was widely known to have many supernatural gifts which he employed for the healing and consolation of his flock. Many knew him as a living saint. After his repose and burial, people came to him to ask for his intercessions on a number of issues. The account of miracles received through his intercession were so many that were compiled into a book.

When his casket was opened 28 years after his repose his body was found to be incorrupt. Now his relics – his incorrupt body – lies on a glass urn in the church, visible and available to all; it is still incorrupt 45 years after his repose. I go there often to ask for his prayers. I kiss his icon, kiss his urn, lean over the urn, look at his hands, I talk to him just as I would if he were breathing and speaking to me right there. Why? Because he is alive. He answers our requests for prayer and intercession, just like he did when he was a living bishop. He continues his ministry, now in the presence of Christ. And so there is a huge, beautiful icon right over his relics there at the church. And obviously I have an icon of St John in my prayer corner.

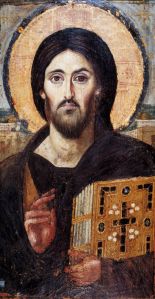

In my prayer corner, I have one icon of the Risen Christ (the one from St Catherine’s monastery), and an icon of the crucified Christ under it (the one from St Francis of Assissi). Around those two central icons, I have one icon of St John Maximovitch, one icon of St John of Kronstadt (who has spoken to me greatly through his writings), one icon of St Michael the Archangel (who defends me in battle), 2 icons of the Theotokos (my Mother), one icon of St Catherine (my daughter’s patron saint) and one icon of St John Chrysostom. So out of my 10 icons on the wall, only two are of Christ. So I guess you can accuse me of loving saints more than Christ on a ratio of 5/1.

I would laugh.

As to St. Phanourious and cakes, again, this is a side issue. Even if you are offended by people asking for the prayers of one whom they might not know much about, but who was obviously revered in ancient times, this could potentially have to do with superstition, not idolatry. And superstition has always been in Israel and in the New Israel. It is in the Protestant church as well. Some people think that if you pray a formula, a “sinner’s prayer” that is all that is necessary to ensure salvation. That is superstition. Some people think that sticking a “in Jesus’ name” after a prayer is the proper formula for make a prayer acceptable to God. That is superstition. Some people thing that if they have daily “quiet time” and read x number of chapters from the Bible, God will necessarily bless them in the particular ways they want. That is superstition. Some people pray with televangelists and put their hands on the screen of the tv. That is superstition. Some people think if you faithfully pay tithes God will necessarily bless you a thousand fold, as a formula. That is superstition. I could go on and on and on.

Should we then remove the Jesus’ name from prayers? Should we not read Scripture as often as possible? Should we not have teachers who can use media to teach? Should we not support the Church with the firstfruits of what God has given us? I don’t think so.

Anyway, I have attempted to give a *very succinct* theological and historical account for the issues of the 7th Ecumenical Council in my post. I hope that has been helpful. If you do want to continue to think about how the 2,000 year old practice of the Church concerning iconography could potentially be beneficial (or not) to you, I recommend you take your time and read some good resources on the meaning of icons, the Communion of Saints, etc. Also, I recommend reading the Church Fathers (e.g., Ignatius, Irenaeus, Cyril of Alexandria, the Cappadocian Fathers, Athanasius, Augustine, etc.) and get a sense of how the early Church lived its spirituality – including prayers for the “dead,” modeling of virtues in the saints, etc. It is only in a more holistic approach that the use of icons can make more sense.

Hope that helps.

I think is great theology, but most of all now I want to eat the cake. Thanks!

[…] For more on icons, see my post “Worshiping Images? Iconoclasm and the 7th Ecumenical Council.” […]